The Bookest

The Many Daughters of Afong Moy

Published Jan 07 2023

I picked up Jamie Ford’s The Many Daughters of Afong Moy from a recommendation by @latinarebels on Instagram, and I was not disappointed. The Many Daughters of Afong Moy spans almost 250 years and over seven generations of Afong Moy and her family’s lives as they navigate forced immigration, social expectations, violence, identity, and the reconciliation of the trauma they and their ancestors have faced. The overarching exploration of this book brilliantly captures the transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, the transgenerational trauma that is inevitably passed from one person to another, and the way this trauma lives in the body and shapes who we are. Thankfully, Ford doesn’t just leave us with a depiction of trauma and its inheritance, he also imagines a future where deep healing from transgenerational trauma is possible.

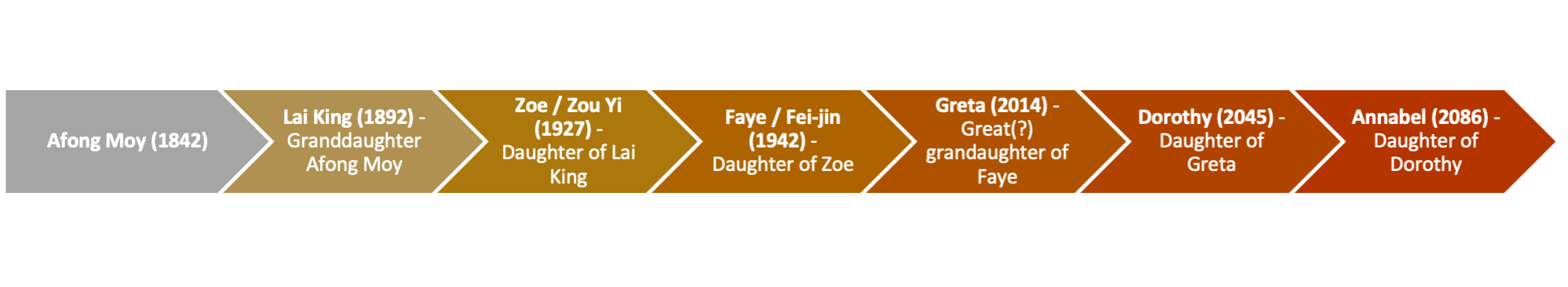

In a series of short stories organized nonchronologically, the reader is slowly presented the intertwined stories of Afong, Lai King, Zoe, Faye, Greta, Dorothy, and Annabel. The nonchronological order captures a natural rhythm of storytelling while also depicting the non-linear impact of trauma. As the reader makes their way through each chapter, the sequence of the book emphasizes the “echoes,” as a later chapter is titled, of each woman’s story within another’s. Sometimes these “echoes” are actual visions of another timeline and other “echoes” are similar events, such as Dorothy realizing her daughter is drawing the same exact plane, possibly a P-40 flown by Americans hired by China during WWII, Dorothy drew as a girl.

Throughout the book, Ford does a brilliant job capturing the painful paradox of those living with the aftereffects of trauma. Often those with past trauma want the trauma to remain buried and forgotten, like Lai King when she thinks about losing her mother, father, and home to the plague, “Lai King’s heart ached for all the things she wished she could forget.” Because our body wants to protect us, the memory of these painful experiences become ingrained in our bodies to help us avoid future pain if possible. The exact opposite of what Lai King, and most of us, want. If one can work through the pain, though, there is also some freedom in learning about our history and the intricate factors that have shaped who we are. In Afong Moy, Dorothy’s therapist recommends an experimental trial of epigenetic therapy led by Dr. Shedhorn. Dr. Shedhorn has developed a process that allows patients to identify and explore their transgenerational epigenetic inheritance and the accompanying trauma to address anxiety, depression, PTSD, and other mental illnesses that may be linked to this trauma. When Dorothy’s partner asks how her sessions are going, Dorothy thinks: “…feeling okay after a lifetime of feeling everything—rage, grief, anxiety, sadness, confusion, disconnection, and longing—to just feel okay was as wonderful as it was unfamiliar. She felt intoxicated by normality.” Though the lived and remembered trauma is painful, processing the trauma and finding some sense of “normality” is a blessing. Something those of us who’ve gone through or are currently undergoing therapy can certainly agree with.

One of the most captivating parts of Afong Moy is the constant emphasis of interconnectedness. Here, interconnectedness is not so much rebirth, but a thread of deep connection between generation. A thread that points to death as a shift in existence. At first, Dorothy thinks of this interconnectedness as a dilution of the self, “Dorothy imagined herself as a copy of a copy of a copy. Each version less sharp, less clear, more muddy, blurry around the edges of happiness and contentment.” However, Dr. Shedhorn explains to Dorothy that “each generation is built upon the genetic ruins of the past. That our lives are merely biological waypoints. We’re not individual flowers, annuals that bloom and then die. We’re perennials. A part of us comes back each new season, carrying a bit of the genus of the previous floret.” In this context, the self is a confluence of the individual, our ancestors, and the seemingly infinite events that have led to our existence with almost unbelievable precision. The only part that makes any of this miraculous occurrence believable is the unlikely fact we’re here. Each of us only new in form but ancient in content; always carrying a part of the past.

The Many Daughters of Afong Moy underscores the beauty of the interconnectedness within and amongst each other, but it also emphasizes the weight of this responsibility for each new generation. From the time Afong Moy is sent to America by her dead husband’s family in 1842, each of Afong’s relatives had to carry the weight of their past along with their own. Not until over 200 years had passed, during Dorothy’s time in 2045, did any of Afong’s family members have the tools to safely and effectively process the trauma the prior generations experienced to finally break the cycle. And this reality, hoping that our children and our children’s children will have more than us, have better than us, is a bittersweet thread that links these stories together. It brings a deeper understanding to all the pain our ancestors experienced—even those from recent generation—with little to no access to proper care and healing.

The Many Daughters of Afong Moy is powerful, successfully navigates a wide breadth of time, and fruitfully portrays complex themes. Lai King says, “‘Ghosts aren’t always bad. Sometimes they’re just our ancestors checking in on us.’” The ghosts of the past surround us, and their echoes reverberate within the microcosm of the self ultimately shaping who we are. If we’re lucky, we might even see a ghost or two, and welcome them.